Mint Rarity Ratings:

| Axbridge | R10 |

| Aylesbury | R10 |

| Barnstaple | R5 |

| Bath | R2 |

| Bedford | R3 |

| Bedwyn | R8 |

| Berkeley | R10 |

| Bridgnorth | / |

| Bridport | R6 |

| Bristol | R3 |

| Bruton | R8 |

| Buckingham | R9 |

| Bury St Edmunds | R6 |

| Cambridge | R2 |

| Cadbury | R10 |

| Caistor | R10 |

| Canterbury | R1 |

| Castle Gotha | R9 |

| Chester | R2 |

| Chichester | R2 |

| Cissbury | R9 |

| Colchester | R2 |

| Crewkerne | R9 |

| Cricklade | R7 |

| Derby | R7 |

| Dorchester | R6 |

| Dover | R1 |

| Droitwich | R10 |

| Exeter | R2 |

| Frome | R10 |

| Gloucester | R3 |

| Grantham | R10 |

| Guildford | R8 |

| Hasting | R3 |

| Hereford | R4 |

| Hertford | R2 |

| Horncastle | R10 |

| Horndon | R10 |

| Huntingdon | R3 |

| Ilchester | R5 |

| Ipswich | R3 |

| Langport | R8 |

| Launceston | R10 |

| Leicester | R3 |

| Lewes | R2 |

| Lincoln | R1 |

| London | R1 |

| Lydford | R3 |

| Lympne | R5 |

| Maldon | R3 |

| Malmesbury | R7 |

| Melton Mowbray | R10 |

| Milbourne | R10 |

| Newark | R10 |

| Newport Pagnell | R10 |

| Northampton | R3 |

| Norwich | R1 |

| Nottingham | R6 |

| Oxford | R3 |

| Pershore | R10 |

| Peterborough | / |

| Petherton | R10 |

| Reading | R10 |

| Rochester | R3 |

| Romney | R3 |

| Sandwich | R3 |

| Stamford | R1 |

| Salisbury | R2 |

| Shaftesbury | R3 |

| Shrewsbury | R4 |

| Southampton | R3 |

| Southwark | R1 |

| Stafford | R4 |

| Steyning | R3 |

| Sudbury | R4 |

| Tamworth | R7 |

| Taunton | R6 |

| Torksey | R9 |

| Totnes | R4 |

| Wallingford | R3 |

| Wareham | R3 |

| Warminster | R9 |

| Warwick | R5 |

| Watchet | R7 |

| Wilton (Wiltshire) | R2 |

| Wilton (Norfolk) | R9 |

| Winchcombe | R8 |

| Winchester | R1 |

| Worcester | R3 |

| York | R1 |

The Monarchs of Later Anglo-Saxon England

Æthelred II ‘The Unready’ – 978-1013/1014-1016: The eldest son of Eadgar, Æthelred became king at the mere age of 12 following the brutal murder of his half-brother Edward. Young and easy to manipulate, he came to depend on his councillors for their prudent advice – an aspect in which they badly let him down. Though his reign is noted for its economic reforms and a high standard for the English coinage, it was marred by Scandinavian raids, periods of acute social instability and famine. Initially adopting a policy of paying the invaders to go away, Æthelred abruptly U-turned in 1002 and massacred many ethnic Danes resident in England. This policy backfired spectacularly, actually causing more Scandinavians to take up arms against him. Displaced from the throne in 1013 by Swein Forkbeard, he briefly returned to rule for a second time in 1014 after the latter’s untimely death – only to die himself shortly afterwards.

Cnut ‘The Great’ – 1016-1035: A prominent Scandinavian prince and junior member of the Danish royal house, Cnut spent much of the early 11th century as an active participant on raids directed at England. In 1013, his father Swein Forkbeard invaded England and became its king by dint of conquest – though died shortly afterwards. Cnut was forced to retreat back to Denmark, but returned to England in 1015. Defeating the English at Assandun in 1016 and forcing a settlement, Cnut eventually succeeded to the throne of all England. An outwardly pious man, he gave generously to religious houses during his reign and went on pilgrimage to Rome – despite being a murderous bigamist. During his near twenty-year long rule, he came to unite England, Denmark, Norway and part of Sweden into the powerful but short-lived ‘North Sea Empire’.

Harold I ‘Harefoot’ – 1035-1040: The eldest son of Cnut, Harold’s strange nickname derives from his alleged fleetness of foot in hunting. Despite being some years older than his half-brother Harthacnut, Harold was not fêted to be Cnut’s immediate successor, as his mother Ælfgifu was of lesser status. Despite this, Harold took control of England following Cnut’s death – pressuring the nobility to support his claim and taking advantage of the fact that Harthacnut was busy suppressing several rebellions in Scandinavia. Though initially conceding to the division of England between Harthacnut and himself, Harold would go back on his word and declare himself sole ruler after only two years of power-sharing. In 1036 he easily quashed an attempt by the exiled sons of Æthelred II to raise rebellion – brutally executing one in the process. He died suddenly in 1040, an unexpected occurrence given his relatively young age.

Harthacnut – 1040-1042: Harthacnut was Cnut’s son by Æthelred II’s widowed queen – Emma of Normandy. As such, he enjoyed premier status as a ‘proper’ prince, both of his parents being duly classed as royalty. Unable to travel to England on the death of Cnut due to uprisings in Scandinavia that required his attention, Harthacnut was forced to accept the rule of his lower-born brother over England as he sought to stabilise the situation. Although initially planning to invade in 1039, his half-brother’s premature death resulted in a relatively peaceful transfer of power. However, Harthacnut exacted his vengeance by having Harold’s body dug up and scattered. His rule was short but nonetheless bloody – characterised by high taxation and friction in the upper echelons of his government. A man who often ate and drank to excess, it is perhaps no surprise that Harthacnut died young at a wedding party, drink in hand!

Edward the Confessor (1042-1066): One of the youngest sons of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, Edward is formally recognised as the last proper member of the House of Wessex. Forced to flee England as a youth after the invasion of Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut – he spent many years exiled on the continent. An abortive attempt to invade and regain power in 1036 resulted in nothing, but in 1041 he was formally invited back to England to take the throne by his half-brother Harthacnut – the last Danish king of England. Crowned in 1042, Edward’s reign has long divided historians. Some argue that he was an effective ruler able to enact aggressive foreign policy and defend his borders, while others point out his over-dependency on the Godwins to keep order and maintain his position. Having no heirs of his own gave rise to rumours of voluntary celibacy, a factor which emphasised his supposed personal piety and gave rise to his epithet ‘the Confessor’ – though this caused a succession crisis. He supposedly offered the throne initially to Duke William of Normandy, but then ratified the succession of Harold Godwinson on his deathbed. He was canonised in 1161 by Pope Alexander III, his saint-cult persisting in England till the 14th century.

Harold II ‘Godwinson’ (6th of January 1066-14th of October 1066): The last Anglo-Saxon king of England, Harold was the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex – Edward the Confessor’s right-hand man. Though Godwin and his family fell out of favour with Edward during the early 1050’s, this was but a temporary setback. His father died in 1053, and Harold took up the mantle as Earl of Wessex – assisting Edward greatly in driving back the Welsh and calming the northern border with Scotland. In 1066 Edward died, naming Harold his successor on his deathbed. However, he had previously favoured William of Normandy – causing the latter to prepare for invasion to defend his ‘right’. Arguably the most famous part of Harold’s short reign is its last month. Marching north to confront an invasion force assembled by the Danish king Harald Hardrada and his own traitor brother, Harold won a spectacular victory at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. However, William of Normandy landed on the south coast shortly afterwards, and he was forced to march back down the length of the country with a tired and depleted force. The decisive moment came on the 14th of October 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, where despite a terrific struggle Harold’s forces were defeated by William – an event famously depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. Harold was killed during the battle, and the throne subsequently passed to William – who became William I of England.

Late Anglo-Saxon part II: Æthelred II to the death of Harold II.

Our story starts in the year 978, with Æthelred the newly anointed King of England at the mere age of 14. The second son of Eadgar and member of the so-called ‘House of Wessex’, he had probably been placed on the throne thanks to the conniving of his relatives and ministers. His elder brother, Edward, had been brutally murdered after just three years of rule. Whereas the reign of Æthelred’s father Eadgar had been stable and peaceful, it is during Æthelred’s rule that the fortunes of England as a nation state take something of a downturn.

A common historical trope is that Æthelred was a tremendously bad king, born out of his epithet ‘the Unready’. However, this is a somewhat grotesque simplification – ‘Unready’ derives from the Anglo-Saxon word unræd, which means ‘ill-counselled’. Already ruling as a child-monarch, Æthelred would likely have depended heavily on his advisors and counsellors – and as such it is unsurprising (and certainly not entirely his fault) that he struggled to rule effectively. As some historians have quite rightly pointed out, the unique challenges he was presented with would have been difficult to deal with for any monarch. While Medieval writers largely vilified him, modern historians have (to a degree, at least) somewhat rehabilitated aspects of his character based on a wider body of evidence. For all the contention, it is undeniable that Æthelred succeeded to a degree through difficult circumstances – one particular success being his coinage reforms which perfected the cyclical Renovatio Monetae (coinage reissue) and elevated its standard, considerably.

The ancient adage of ‘hard times breed hard men, easy times weak men’ is oft repeated and perhaps cliched – but it is arguably appropriate to the closing decades of the 10th century. With the last ‘Viking’ king of York deposed in the 950’s and most instability since then focused internally, it is perhaps fair to say that many of the ministers and nobles who surrounded Æthelred in the late 970’s had relatively little to no experience in dealing with invaders from across the North Sea. Certainly, none of them would have been alive when Alfred beat the Danes at Edington, not even when Edward the Elder and Æthelflaed reconquered the Danelaw and stamped English authority back onto the so-called ‘five boroughs’ in the Midlands. From 980 onwards, perhaps having heard of Edward the Martyr’s death, Scandinavian raids recommenced on Britain. Although these were initially minor, they escalated in 986 – when an inconclusive pitched battle was fought with the English during a large raid on Devon.

However, the worst did not come until 991 – when a large force landed in Essex and soundly defeated Æthelred’s forces at the Battle of Maldon. With England effectively at the mercy of the Scandinavians, Æthelred was forced to accept a painful settlement involving the payment of large sums of money – Danegeld’ (literally; ‘Dane payments’) – to make the raiders go away. This made little difference, and raids up and down the coast continued until 994 – when in the aftermath of an attack on London, Æthelred began negotiations with the leaders of the Danish fleet. An ornate diplomatic ceremony involving further payments, symbolic exchange of hostages and the baptism of a Norwegian prince called Olaf Tryggvason culminated in the agreement that the Danes would not return for the purpose of violence. His symbolic departure (never ever to return to England) is contrasted by the many Danish mercenaries who chose to enter Æthelred’s service, these being mainly billeted on the Isle of Wight. A few years of peace followed, but this was ultimately short lived. In 997, the allure of more profitable plunder appears to have incentivised the Danes in Æthelred’s employ to revolt – and they again ravaged the south coast from their base on the Isle of Wight. This took place virtually constantly for the next four years, excepting 1000 – when the fleet instead targeted Normandy before returning to England the next year.

By 1002, Æthelred had clearly had enough. Promises, treaties and payments had not worked – so he tried a drastically different tack. On November the 13th, he initiated what has come to be known as the St Brice’s day massacre – whereupon he ordered that all the Danish men in England be taken and killed. The extent of this order to commit genocide is hotly debated, but it is unlikely to have been carried out in every town (especially in Eastern England) due to the high number of Scandinavian-descended inhabitants. This notwithstanding, pieces of both documentary and archaeological evidence strongly suggest that in some areas Danes were killed on Æthelred’s orders. Perhaps the most chilling of these is the mass grave discovered in the quad of what is now St John’s college Oxford, where the bodies of some 35 young and adult men were discovered. Their bones show evidence of a frenzied attack, demonstrating multiple stab wounds from all angles, ‘defence’ injuries and a number of decapitations. Charring present on some bones indicates that at least some of the bodies had been partially burned, perhaps in a building fire. Isotope analysis suggests that virtually all were of Scandinavian origin, and the C-14 date of c. 960-1020 retrieved from some of the bones brackets the date of the St Brice’s Day Massacre. Although we cannot be certain that this assemblage of human remains relates to this event, it is more likely than not based on the current evidence available.

If Æthelred had intended this massacre to dissuade further Danish attacks on England, it backfired spectacularly. In 1003 King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ of Denmark invaded England and proceeded to ravage the country – sacking Norwich and Thetford in 1004 before departing. Despite relatively quiet years between c. 1005 and 1008, Danish forces returned again in 1009 – led by Thorkel the Tall, a warlord who harried the country continuously till around 1012 – when his expedition was finally bought off with yet another enormous payment. These virtually continuous tributes between the years of c. 991 and 1012 are the primary reason why coins of Æthelred are today more common in Scandinavia than England – with huge numbers deposited in hoards and even travelling down inland rivers into places like Estonia, western Russia and the Baltic through trade networks.

In 1013, Sweyn launched a full-scale invasion of England and declared himself its king – forcing Æthelred into exile on the continent. Unfortunately, his rule was short-lived, as he died suddenly later in the year. The Danish forces in England widely supported his son Cnut as successor, though many among the English nobility are known to have approached Æthelred and offered their support if he acquiesced to their many demands for reform – an interesting early example of a king effectively being held to account by his subjects. Æthelred subsequently returned to England and resumed hostilities against the Danes, retaking much of the country largely thanks to assistance from an unexpected ally – the soon-to-be King of Norway, Olaf Haroldsson. By April 1014 Cnut’s position was virtually untenable, being outnumbered and with his allies utterly defeated. He therefore departed England and returned to Denmark to lick his wounds. The security of England had to all intents and purposes been saved at the last moment – though only temporarily.

For a period of around a year from the summer of 1014, a degree of stability persisted. Now back in control of the country, Æthelred began to stamp his authority on troublesome areas such as the old ‘five boroughs’ – which given their historically Danish associations had unsurprisingly declared for Cnut along with the inhabitants of the old Lincolnshire kingdom of Lindsey. Executing several of the high-status thegns who effectively acted as administrators for the area, Æthelred’s son Edmund (a capable military leader and now next in line to the throne, thanks to the death of his two older brothers) saw an opportunity to increase his own power over the region and forcibly married one of the widows resulting from these punitive measures – a woman called Ealdgyth, a move which led the old ‘five boroughs’ to publicly submit to him. This union was opposed by Æthelred, who had attempted to have her interned in a nunnery for the rest of her life in order to ‘remove’ her from the pool of potential marriage alliances that his rivals could draw on.

In the summer of 1015, Cnut returned to England with a new army. However, what he encountered on his return was anything but a stable situation. Perhaps tired of his father’s policies or disillusioned by his harsh reprisals exacted on the Midlands, Æthelred’s son Edmund had engaged in open rebellion against him – setting himself up in the Danelaw and dubiously titling himself as an Earl. It was to this divided England that Cnut opportunistically returned in 1016, and although father and son briefly put aside their animosity to unite against the invader, Æthelred died relatively quickly afterwards – probably worn out from over a decade of acute social strife. Edmund succeeded him to the kingship, but on that subject a divide emerged amongst the English nobility. While Edmund was supported by the clergy and citizens of London and Wessex, the rest of the Witan (council of elders) favoured Cnut’s succession.

Following a series of inconclusive engagements throughout the summer of 1016 that ranged across the breadth of southern England, the ‘final showdown’ between Edmund and Cnut took place at Assandun (the location of which is disputed between the Essex villages of Ashdon and Ashingdon,) in 1016. At this battle Edmund was decisively defeated, although Cnut acknowledged Edmund’s prowess in warfare – hence his nickname ‘Ironsides’. It seems that in the aftermath of this battle, both men ratified a treaty that gave them joint governance of the country – Cnut taking control of Mercia and Northumbria, while Edmund retained his political stronghold of Wessex (including London). However, the story does not end there. On the 30th of November 1016, having jointly reigned alongside Cnut for only a matter of months, Edmund died – though sources disagree whether this was from natural causes or a case of murder. Either way, it removed the last obstacle to total kingship over England from Cnut’s path, and he quickly assumed control of the entire country.

If there is a person in the later Anglo-Saxon history of England who can be considered to have had a meteoric rise to power, Cnut is probably the prime candidate. A veteran of several Scandinavian incursions into England in the first years of the second millennium, he was the son of Sweyn Forkbeard and grandson of Harald ‘Bluetooth’ – a seminal figure in the creation of the Danish state (and of course, a member of the Danish royal house). Although his successful accession to the throne of England was a major coup in his fortunes, it is only in the years following his coronation there that Cnut’s power began to truly expand on an international scale. In 1018, he became king of Denmark following the death of his brother, Harald II. Not content to just rule over part of Scandinavia, he pressed forward with military expansion and by 1028 had also acquired the throne of Norway. He even managed to conquer some Swedish territories, which had resisted him alongside the Norwegians. It is therefore not unreasonable to suggest that Cnut deserves his nickname ‘the Great’, despite the fact that after his death many of these new acquisitions regained their independence. The confederation of England, Denmark and Norway by Cnut effectively gave him power over a great swathe of northwest Europe. This grouping has come to be known as the North Sea Empire, which despite only existing for a little over a decade became a great interconnected trading power. In effect, it was an early example of a maritime monarchy or thalassocracy – a disparate realm dependent on and simultaneously interconnected by the sea-lanes which effectively served as the 11th century equivalent of modern motorways or autobahns.

Despite the fact that England represented just one of Cnut’s assets, so to speak, he governed it both energetically and ably – albeit also brutally. After taking power, he quickly aligned himself with the now deposed House of Wessex through marriage to Æthelred’s widow, Emma of Normandy (a bigamous marriage, given that he already had one wife). Potential for rebellion was stamped out early, with reprisals undertaken against those who had failed to support him during his first bid for power in 1013-14. Several of Æthelred’s surviving heirs were also outlawed, and one was murdered on a trumped-up charge of treason. His actions caused, in effect, a miniature diaspora of Anglo-Saxon nobility into Europe. Although some (such as Æthelred’s two sons Alfred and Edward) went into exile with Æthelred’s brother-in-law Richard, Duke of Normandy, others ended up farther afield. For example, Edmund Ironsides’ two sons began a series of fascinating adventures that brought them all the way to assisting the exiled king of Hungary into retaking his throne, one of them even marrying a Hungarian princess and settling down there for good.

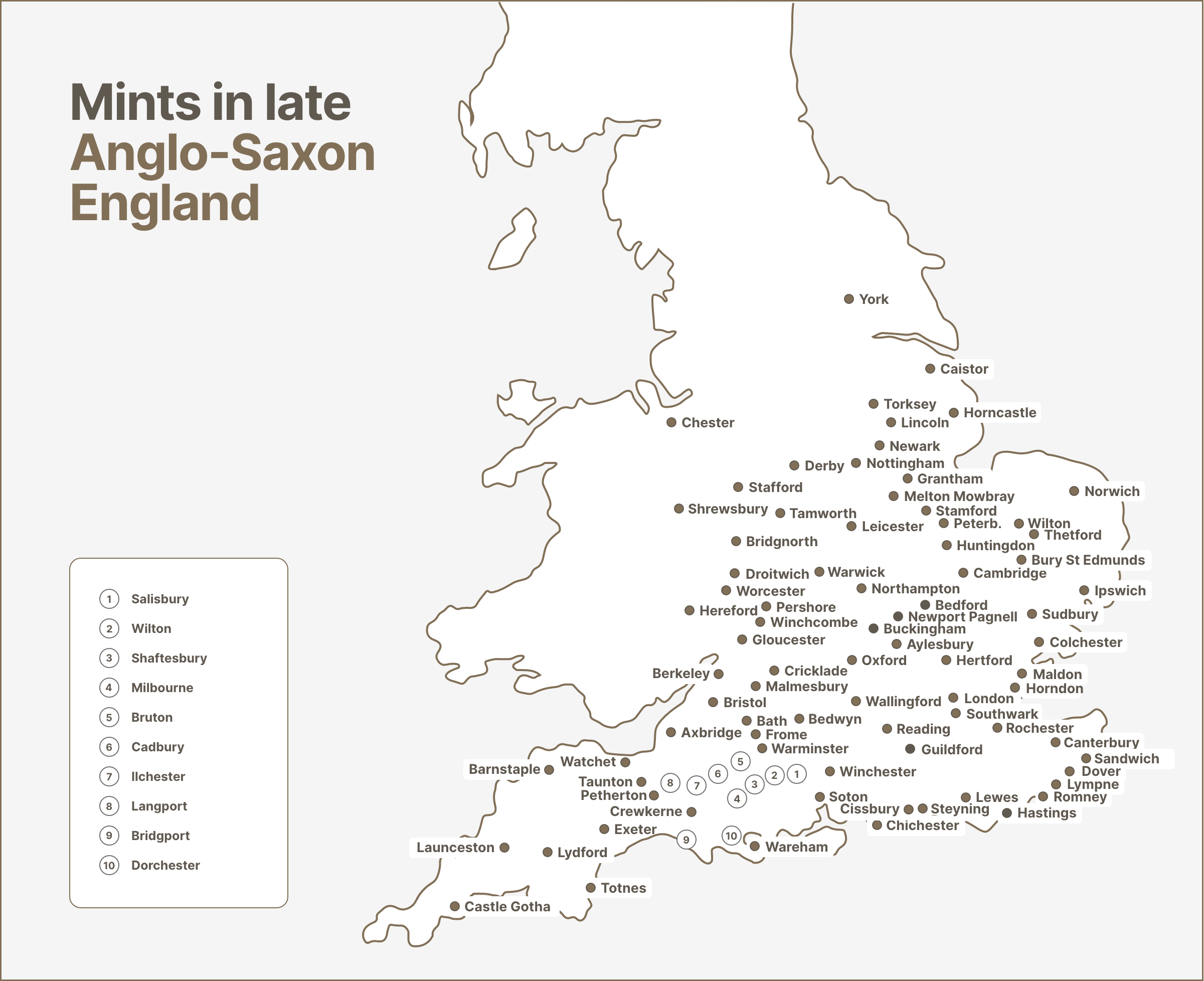

Once established, Cnut undertook a number of practical and reforming measures to ensure the stability of the country. Exacting a last, huge Danegeld in 1018, he disbanded most of his army and sent them back to Scandinavia – thwarting the temptation of future attacks by instituting a special annual tax to ‘fund’ (or rather, keep sweet) current standing and previous members of his armed forces. Such a tax would require the production of even more money, and perhaps it is no surprise therefore that under Cnut the total number of mints in operation is thought to hit its peak – with approximately 70 churning out high quality silver pence for the duration of his reign. Continuing with matters domestic, he publicly upheld the law-codes of King Eadgar in his general 1019 letter to the people of England, authored as a kind of royal proclamation. In addition to this, Cnut also re-organised the administrative Anglo-Saxon ‘shire’ system – effectively dividing the country into four units based on the old boundaries of Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia. Each region was now to be administered by a single Earl, who in turn reported to Cnut himself. Though initially drawn from Scandinavian-descended nobles in Cnut’s inner circle, over time native Anglo-Saxon nobles began to curry favour, including one Godwin who would become Earl of Wessex – the father of a particularly important figure who appears a little later in our story.

An apparently pious man despite his bigamous marriage and arguably un-Christian behaviour towards problematic survivors of the old regime, Cnut heavily invested in the construction and maintenance of religious houses – including paying for the repair of those destroyed or damaged by previous Scandinavian raids through the last years of the 10th century and early years of the 11th. In 1027 he presumably felt confident in his position, as he went on pilgrimage to Rome. Coupling this religious visit with the opportunity to do some European diplomacy, he was able to negotiate important benefits for other ordinary pilgrims. These included exemptions from tolls and increased security on thoroughfares to ensure their wellbeing. Indeed, Cnut’s desire to appear a loyal and humble servant of God is the subject of arguably the most famous story concerning him. Fed up with the adulations and sycophancy of those surrounding him, he made a very literal point that he was ‘just’ a mortal man by sitting in the sea at Bosham, Sussex, and letting the tide engulf his throne. Not even he, ruler of three countries and an uncountable number of people, could thwart the will of nature – and by default, God!

Cnut died in 1035 and the North Sea Empire partially disintegrated, with Norway’s original royal house returning to claim their ancestral kingdom once again. The next seven years would be one dominated largely by the actions of his two eldest surviving sons – the half-brothers Harold ‘Harefoot’ (named so for his alleged swiftness of foot in hunting, of which he was apparently very fond) and Harthacnut. However, despite their shared blood, there was no brotherly love nor interest in cooperation between the two. The key issue between these two sons of Cnut lay in the female side of the line. Whereas Harold was the elder, his mother was Ælfgifu of Northampton – a Mercian noblewoman who was Cnut’s first wife. On the other hand, while Harthacnut was junior, his mother was Emma of Normandy – Æthelred’s widow and as such Cnut’s ‘proper’ Queen. As such, Harthacnut’s status was considered by many to be superior to that of Harold.

When Cnut died, Harthacnut was ruling over Denmark in his stead – but could not immediately return to England for his coronation due to regional instability in Norway and Sweden that threatened to spread into Denmark. He was therefore forced to remain in Scandinavia until a firm degree of control had been established. Although Harold had the geographic advantage in that he was in England at the time, a major spanner was thrown in the works by Æthelnoth – the Archbishop of Canterbury. Perhaps fearing civil war, he refused outright to crown Harold. The situation was not helped by the fact that according to the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, the Witan agreed that Harold should rule – despite disagreement amongst the Earls on this matter. The stalemate was initially broken by a compromise – Harold ruling north of the Thames and Harthacnut in the south. Evidence of this agreement may be visible numismatically, for example – Harold’s ‘jewel cross’ type pence (mainly from mints north of the Thames) are also struck in the name of Harthacnut (which are by contrast mostly from mins in the south) – implying their simultaneous issue. This situation appears to have lasted from approximately 1035-1037, after which Harold took sole control of the entire country in a bloodless coup. Historical sources attribute this success in part to the efforts of his mother Ælfgifu, who seems to have spent much of her time following Cnut’s death rousing support for her son – some of it in the form of bribes or promises of increased political power. Harthacnut was in all likelihood not particularly impressed with this turn of events, though there was little he could do about it – isolated as he was in Denmark.

Perhaps another reason for Harthacnut’s lack of immediate action was an astute reading of the English political situation, in that there was clearly widespread support for Harold’s rule amongst the English nobility (and therefore any serious attempt to take direct control was likely to hit some fairly big obstacles). In 1036, some of the exiled House of Wessex had attempted to make a comeback – with disastrous consequences. Alfred and Edward, the sons of Æthelred, had landed in England with a small force. If their objective was to take control of the country, it failed miserably. Alfred was quickly captured near Winchester and his small bodyguard dispatched with ease. Captured by the morally fickle Earl Godwin of Wessex, he was handed over to Harold’s men. En-route to Ely he was punitively blinded, and he died soon afterwards. Edward fared somewhat better, and escaped back to the Continent. This attempt to return had failed – but it would by no means be his last attempt. We shall hear more of him in due course.

In March 1040, Harold died in his late twenties or early thirties. The Encomium Emmae Reginae (a somewhat biased historical chronicle commissioned by Emma of Normandy, which portrayed Harold as a fratricidal maniac) suggests that it was the English nobility who instigated steps to have Harthacnut succeed Harold when the latter first fell ill in 1039. It appears to be the case that in this same year he was already preparing for a full-scale invasion of England, but held back after hearing that Harold was unlikely to recover from his illness. Instead, he apparently began making preliminary arrangements – including liaising with Emma near what is today Bruges. Thus, when Harold finally died – Harthacnut was ready to take power. Following the official ‘offer’, as it were, from the English envoys, he crossed from Scandinavia with a fleet of around sixty ships – landing at Sandwich and paying off the crews. Although Harthacnut and Harold had never seen eye to eye for various reasons, it appears to be the case that the murder of Alfred, Harthacnut’s half-brother, had deeply affected him. Despite the fact that Harold was dead and as such could not be afforded any meaningful punishment, Harthacnut ordered his corpse excavated and scattered after a symbolic ‘beheading’ in public.

From Harthcnut’s perspective, he had taken over the country and finally (from his point of view anyway) succeeded to his birthright. However, the situation improved little for the ordinary English people – and points of friction quickly emerged. Firstly, Harthacnut seems frequently to have quarrelled with his advisors about the process of rule, since in Scandinavia the king usually had absolute authority. In England, by contrast, the king was expected to rule both alongside and in co-operation with his council of leading advisors. His expansion of the standing English navy (necessary, now that his realm stretched across the North Sea) came at enormous cost to taxpayers. The huge fiscal burdens being placed upon people came to a head in a particularly nasty incident at the city of Worcester, where over-zealous tax collectors and their helpers were turned upon and murdered by the enraged local population. Harthacnut ordered the town be harried (aka, burned and then the population killed) but they fortified their position and defeated the forces sent to subjugate them. Harthacnut, evidently impressed by the resistance they had put up, pardoned everyone involved and took no further action. Despite the outcome, this situation indicates the extent to which people were becoming disenchanted with his vigorous money-raising policies.

Comparably with his half-brother Harold, Harthacnut seems to have been a sick man. Some sources suggest that even by 1041 (just a year into his reign), he had become very unwell. The 12th century historian Henry of Huntingdon portrays him as the victim of his own gluttony, claiming that he was a trencherman of some renown who ate and drank prodigiously in equal measure. Other writers have suggested a more chronic and severe condition like tuberculosis. Irrespective of what afflicted him, Harthacnut’s reign was to a degree influenced by a great deal of uncertainty – both in regard to his day-to-day life, and the question of succession (given that he had neither a wife nor children). It is against this background of uncertainty that some historians argue for the return Æthelred’s sole surviving heir Edward, and his formal invitation back into the English royal fold. The man who had returned after the death of Cnut and subsequently exiled again was now being given a place at the negotiating table. Logically, Edward was the only real remaining choice who would likely be accepted by the English people. He was the sole surviving son of Æthelred II and Emma of Normandy, Cnut’s stepson by default and as such Harthacnut’s half-brother. Whether he was invited back by Harthacnut willingly or at the behest of his English advisors is a more complex question, but documentary evidence shows that by 1042 Edward was being recognised publicly as Harthacnut’s brother and successor. Some have suggested that Emma herself was instrumental in ensuring Edward’s succession, the achievement of which would allow her to continue wielding significant political power.

Conveniently, perhaps too much so – Harthacnut died in 1042. Sources describe how he passed away suddenly at the wedding of one of his thegns, convulsing and falling to the ground after drinking the couple’s health. Some suggest a spontaneous and deadly stroke, though others argue he could equally have been poisoned by an unknown aggrieved party. Upon his death, the briefly re-united realms of England and Denmark were again separated, the latter being taken over by the Norwegian king Magnus until his own death in 1047.

With the re-acceptance of the house of Wessex by Harthacnut, the surviving descendants of Æthelred II had returned to rule again. After a near twenty-year period of continental exile through some of his most formative years, Edward son of Æthelred was now king, and for the first time in almost twenty years it was an English-descended monarch who ruled over England, replacing the Danish dynasty for good.

After Alfred the Great, Edward (posthumously known as ‘The Confessor’ due to his sanctified status and supposed personal piety) is probably England’s next best known Anglo-Saxon king. However, his reign is not generally acknowledged as a particularly positive one. Although Earl Godwin of Wessex had personally ensured Edward’s succession and he had (according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) been welcomed with open arms by the citizens of London, problems began to quickly emerge. Thanks largely to his Continental upbringing, Edward was somewhat biased towards members of his entourage who came from that region – for example, Robert the Abbot of Jumiéges – who travelled back to England with Edward and was duly fast-tracked to the Archbishophric of London. This employment of ‘foreign’ aides and advisors, though relatively few in number, would cause no small degree of resentment through Edward’s reign.

Continental influence went beyond the choice of select advisors and permeated into the very fabric of his domains, perhaps best exemplified by Edward’s great building project – Westminster Abbey, which was erected in the European ‘Romanesque’ style. Although the building was largely reconstructed to its present form by Henry III in the 13th century, parts of the original building still survive. Edward seems to have had a particularly strong connection with the idea of turning London into the true capital city of his realm (as opposed to Winchester, where the Anglo-Saxon kings were traditionally crowned), and it is perhaps in this context that he sponsored the manufacture of what would become the English crown jewels – their place of storage in perpetuity being, of course, Westminster Abbey.

The importance Edward attached to the idea of symbolic kingly regalia and fulfilling the full image of a monarch is clearly visible in two types of penny he issued. Firstly, the ‘sovereign/eagles’ type – the only one of his types issued which shows a full body portrait. On these coins he appears sat on a throne, crowned, holding orb and sceptre. By contrast, on his last type – the ‘pyramids’ issue of 1064-6, Edward is depicted in profile wearing a Byzantine style crown with dangling jewels that hang down to past his ears (pendilia). With ornate and accessorised depictions such as these, he hoped to espouse the very model of a ‘modern’ Anglo-Saxon ruler – adhering to tradition, but also enlightened and aware of new ideas both from the Continent and further afield.

On taking the throne, Edward immediately strengthened his position through tying himself to England’s most powerful family – the so-called ‘Godwinssons’ headed up by Earl Godwin of Wessex. The presence of these new regional governors as instituted under Cnut meant for a change in the power dynamics of how a king exactly went about ruling, and as such Edward was likely keenly aware that he needed to keep them on-side if he wanted to maintain his position. Although Godwin had been placed in his position by Cnut and subsequently implicated in the downfall of Edward’s brother Alfred during his failed insurrection years before, he was too powerful to ignore. Edward initially curried favour in 1043 by promoting Godwin’s son Swein to a junior Earldom in the midlands, following this up in 1045 by marrying his daughter Edith. Even Godwin’s youngest son Harold was awarded an earldom. Edward was investing a great deal into the family which he hoped would provide his right-hand men for years to come. This, as it transpired, would be a grave error.

Despite a relatively quiet early reign, Edward’s reliance on the Godwinssons would unravel dramatically in 1051. Following an incident in which Godwin himself was insulted by the king after a relative’s bid at being promoted to Archbishop of Canterbury went somewhat pear-shaped, he seems to have made his mind up to hamper Edward’s rule in any way he could. As such, during a visit by Edward’s brother-in-law Eustace to the town of Dover and the subsequent violence that arose between townsfolk and members of Eustace’s retinue, Godwin refused to help quell the riots. Knowing perhaps that Edward would use this insubordination to punish him, he went a step further and ordered his sons to mobilise their forces. Edward, obviously furious at the situation spiralling out of control, demanded his other Earls also raise troops to meet the potential risk of civil war.

With battle-lines drawn, the old maggot of Godwin’s treachery against Edward’s brother Alfred was again resurrected by Edward’s close advisor Robert of Jumiéges, accusing Godwin of being a duplicitous and power-hungry traitor. This information being publicly revealed was perhaps a clever tactic intended to divide Godwin’s forces and re-affirm their ultimate loyalty to the king over their Earl. Evidently, it worked – as Godwin quickly baulked from military action and left the country with his entire family for exile in the Netherlands. However, the respite was only temporary – as Godwin returned a year later at the head of an army and forced Edward to re-instate him as Earl of Wessex and his (surviving) sons to their respective positions. Edward, by now in his late forties and probably tired of conflict, acceded to these demands and thereafter took a much more passive role in the governance of England.

The subordination of Godwin against Edward was a watershed moment in Late Anglo-Saxon history, and it did not bode well for future governance of the country. Although Godwin himself died in 1053 after over twenty years on the English political stage, his son Harold would quickly replace him as Earl of Wessex by 1055. By 1057, thanks to unpredicted deaths of the other Earls and the fact that many of their surviving children were underage, Harold’s younger brothers occupied three of the four remaining Earldoms; Tostig in Northumbria, Gyrth in East Anglia and Leofwine as the sub-earl of Wessex. After a period of stagnation, the Godwins were largely back in control of Anglo-Saxon England.

Some historians have suggested that during the 1050’s, Edward largely took an indirect role in the governance of England. Primary sources describe how he turned to churchgoing and hunting, largely withdrawing from political life. However, this is not totally borne out by the historical record. These years were marked by border issues in Wales and Scotland – with Edward’s foreign policies towards these two realms somewhat aggressive in nature. In 1053, he put a price on the head of Welsh prince Rhys ap Rhydderch for raiding into England (which was duly received), and in 1055 Edward and Harold went on campaign together to drive the legendary Gruffyd ap Llewellyn back into Wales – attaining his (temporary) submission. The crossing of Edward’s path with other legendary figures known in popular culture today also occurred in the north, supporting the return of the exiled Malcolm Canmore to the Scottish throne – whose father Duncan I had been usurped and murdered. His killer? None other than the legendary Macbeth or Mac Bethad mac Findlaích, to name him properly in Gaelic – as immortalised almost 600 years later by William Shakespeare. Edward ordered an invasion of Scotland in 1054, and by 1058 Malcolm was on the throne – having established a foothold and defeated Macbeth in battle. These do not seem much like the actions of a feeble, politically disconnected ruler.

Towards the end of Edward’s life, the question turned yet again to that of succession. Despite his marriage to Earl Godwin’s daughter Edith, no children had been born (though considering that following Godwin’s fall from grace Edward had threatened Edith with confinement in a nunnery, this is unsurprising). Some Medieval historians place this lack of heirs upon Edward’s personal piety, suggesting that he had decided to remain celibate on becoming king. Irrespective of the latter, the issue of whom would become the next ruler of England was therefore an urgent one that defines Edward’s late reign, especially given the fact that he was well advanced into middle-age by this point. An attempt was made in 1057 to reconnect with the long-adventuring Edward ‘the Exile’, son of Edmund Ironside and Edward’s nephew, who had spent most of his life in Hungary. However, he died shortly after arriving in London. His young son Eadgar, of whom we shall hear more of later, was subsequently adopted into the English court.

It is at this juncture that we introduce one of the most famous figures in English history to the picture, Count William of Normandy – sometimes known more earthily as ‘William the Bastard’. As a member of the House of Normandy, William was effectively a relative by marriage of Æthelred II – one of his ancestors being Emma of Normandy (and thus, Edward’s first cousin once removed). We have told previously of Edward’s extensive ties to the region, in addition to the fact that William’s father, Count Robert of Normandy, seems to have played a role in protecting Edward and Alfred at his court during their persecution by Cnut. It is therefore very likely that Edward would have known William personally – albeit as a child. Although William’s father died when he was very young and Normandy largely fell into misrule as nobles fought for control of his influence, by the 1050’s William (now an adult) had largely regained control of the region and expanded his territory into Maine, Flanders and Brittany through aggressive diplomacy and political marriage. His quick rise to prominence in addition to previous family ties likely helped catch Edward’s eye across the channel.

Against the background of Earl Godwin’s betrayal, the Anglo-Saxon chronicle states that William came to visit Edward in England around 1051. Whether this trip occurred and what purpose it was supposed to fulfil is actually uncertain, but Norman sources claim that at some point after it, Edward proposed that William succeed him to the throne of England now that Godwin appeared to have burned all his bridges. Historians have argued endlessly about what really happened and what Edward actually intended, some conceding that perhaps a communication breakdown took place. Maybe in 1051, Edward really did intend for William to succeed him – but it seems he changed his mind afterwards. After all, a mere five years after this alleged meeting, the Godwinssons were back at court – so to speak, and becoming more powerful than ever. The Bayeux tapestry fosters the claim echoed by contemporary chroniclers that around 1064, Harold Godwinsson was shipwrecked in Normandy and temporarily taken in by William after being mistakenly arrested. During this trip, Harold is alleged to have fought bravely alongside William during his Brittany campaign, and William seems to have accordingly catered to Harold’s every need. Norman sources claim that during their meeting, Harold swore over a casket of holy relics that he would uphold William’s claim to the throne. It is interesting that no English historical sources mention this event, and thus its occurrence is quite unlikely. As such, it appears to be a blatantly pro-Norman fabrication that (as we shall see) superficially legitimised William’s claim to the English throne.

On the 5th of January 1066, Edward the Confessor died – still childless. Both English and Norman sources agree that on his deathbed he named Harold Godwinsson as his successor, with his wife Edith and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stigand, present as witnesses. However, from the Norman’s perspective, Edward’s proclamation had no legitimacy as Harold had previously sworn to William during his dubious ‘visit’ to Normandy several years earlier that he would support William’s claim to the throne. None of this appears to have deterred Harold, who was crowned on the 6th of January 1066 with the apparent support of both the English clergy and nobility. The quickness of his coronation either implies his desire to be quickly ratified as the new King of England, or conversely suggests that preparations for this event had been going on for some time under the direction of Edward himself. Whichever is the case, the coronation caused great ripples in northwestern Europe. William of Jumieges writes that on hearing of it, William sent an embassy to remind Harold of his obligations – though whether this actually happened or not is unknown. Meanwhile, across the sea in Norway, King Harald Hardrada was pondering his position amid an understanding his predecessor, Magnus, had had with Harthacnut regarding the eventuality that if either died childless the other should inherit both kingdoms. The two-way rivalry had become a three-way power struggle with the potential to get extremely messy indeed.

The spring and most of the summer of 1066 can be seen comparably to the European situation of 1939 – the so-called ‘phoney war’ of World War II. Actual hostilities were initially quite few and far between excepting a few raids in the north by Harold’s exiled brother Tostig (in league with the Norwegians), with military matters mostly pertaining to preparation for future conflict. As with his predecessors, Harold literally stamped his rule on the population through the issuing of many silver pence at a variety of mints – his only type boldly proclaiming ‘PAX’ within a tablet on the reverse. Perhaps he was keen to resolve the issue diplomatically or dissipate worries felt by the local population, given the prominent war-clouds visible on the horizon.

Having supposedly received papal assent for his invasion, William began constructing an invasion fleet in northern France to carry his forces across the channel. Harold, aware that he had the advantage as a defender, called up the local fyrds (militias) and stood ready to receive any attacks on the south coast for virtually the entire summer. Unfortunately for Harold, the fact that most of his forces were ‘called up’ from the civilian population as opposed to representing an independently trained, professional standing army was to be against him. In early September, he was forced to disband a very large part of his forces so that they could gather the harvest in, otherwise the country would face a difficult winter rife with starvation.

With Harold’s brother Tostig assisting him, it is very likely that Hardrada of Norway knew that an attack in the early autumn would probably catch the English off-guard. It therefore comes as no surprise that shortly after Harold’s disbandment of many soldiers he ordered the invasion of northern England. Harold’s northern earls, the brothers Morcar and Edwin, were defeated with their local forces in the Battle of Fulford. As such Harold was forced to march north to confront Hardrada and his traitorous brother. The epic showdown took place on the 25th of September at Stamford Bridge, near York, where the Scandinavians were utterly routed – both Hardrada and Tostig being killed in the engagement. A probably mythical story tells of a giant Scandinavian soldier holding the bridge alone against the English to give his comrades on the opposing bank time to prepare, cutting down many before himself falling to a lance thrust up from below the bridge by a cunning English soldier.

With Hardrada and Tostig liquidated, Harold had rid himself of two major problems in one fell swoop. However, he was to be extremely unlucky. While he and his troops were still recovering in the aftermath of Stamford Bridge, William’s invasion force set sail from the seaport of St Valery-sur-Somme on September the 27th 1066. Although it is unlikely William coordinated with Hardrada and Tostig directly, it is probable that he knew the two had attacked northern England and thus distracted Harold’s attention from the south coast. The crossing was apparently uneventful, and William landed unopposed on the 28th of September at Pevensey Bay, East Sussex. Moving a few miles inland to Hastings, he threw up fortifications and began to raid and pillage the local area – probably in an attempt to make his presence known and bait Harold into a premature move against him. In a secure position, not far from his lines of communication with Normandy, and a strong army at his back – William now was able to turn many of the advantages Harold had previously held against him.

In the modern era, we are well-used to the mores of instant messaging and communication. Through Whatsapp groups, Telegram channels and of course the usual news outlets we are able to learn of events occurring around the world within hours or even minutes. However, it must be remembered that in the time of Harold and William news spread only as fast as a messenger on foot or horseback could travel. As such, having left a large part of his army in the north and back to the south coast – Harold only received word of William’s arrival several days after the battle of Stamford Bridge. The news probably surprised and concerned him in equal measure – he had split his forces, the troops he had were probably tired from their epic march north and his pool of available men was reduced due to the necessity of gathering the harvest. It is for this reason that Harold probably chose to march to London and stay there a week instead of immediately confronting William – he needed time to consolidate his army and consult with advisors.

Around the 12th of October 1066, Harold and his forces left London and marched to a prominent ridgetop near to the modern-day town of Battle, East Sussex – some 6 miles from William’s fortifications at Hastings. This did not dissuade William, who in turn marched out and formed his own troops up. The two armies were probably of similar size (perhaps around 7,000-10,000 men strong), though compositionally quite different. While the English forces were mostly composed of infantry armed with spears, shields, swords, axes and javelins, the Norman army was more diverse – containing infantry as well as heavy cavalry and archers. The choice of ground was a sensible choice on Harold’s part and advantaged the English greatly – the Normans would have to fight an uphill battle against the traditional Saxon ‘shield wall’ – disadvantaging their feared heavy cavalry and reducing the efficacy of missiles.

The date was October the 14th, 1066 – and arguably the most significant event in English history was about to be spelled out, one which virtually every schoolchild knows – the Battle of Hastings. Aside from its status as a defining moment in English nationhood, widespread knowledge of the event is also assisted by its being spelled out in visceral detail on the post-battle Bayeux Tapestry, probably commissioned by William’s half-brother (and co-combatant in the battle itself), Bishop Odo of Bayeux, as a depiction of his personal achievements. Chroniclers attest to the bloodiness of the engagement – the battle apparently lasting from about 9am till sunset. Detailed (and wholly reliable) accounts of the day are difficult to verify, but initial Norman uphill attacks were repulsed effectively by the English for several hours. Early setbacks occurred – some elements of the Norman army (specifically William’s detachment of troops from Brittany) were broken and routed – while a rumour began circulating that William himself had been killed in the fighting. The Bayeux tapestry depicts this pivotal moment in detail – the Duke throwing off his helmet from horseback to show that indeed he was still very much alive and kicking. For all his status as an invader, that William was in the thick of the combat is probably indisputable – his own chaplain, the chronicler William of Poitiers, recounts that several horses were killed from under him over the course of the battle.

Following the rout of the Breton troops, many Saxons apparently pursued them downhill – but were quickly surrounded and killed. This tactic appears to have been adopted ad-hoc, combat followed by contrived withdrawal was utilised expertly by the Normans to slowly whittle down the less-disciplined elements of the shield wall. Despite the employment of this strategy, the English line held. It was apparently not until quite late in the day that the decisive moment came – marked by Harold’s death, probably occurring alongside that of his brothers (and deputies in command) Leofwine and Gyrth. The exact manner of Harold’s death has long been disputed, the Bayeux tapestry being rather ambiguous in what it tells us, as there are two figures that the text ‘here King Harold is killed’ could be referring to. Whereas one figure apparently has been shot in the eye with an arrow, the other is cut down by a charging horseman. The ‘arrow in the eye’ trope as pertaining to Harold is one that does derive from a source dating to the 1080’s, but how truthful/reliable it is is entirely another question.

Now leaderless, their ranks heavily depleted (having potentially suffered as many as 4,000 killed) and exhausted after an entire day’s fighting – the English broke and began leaving the battlefield en masse. The final scene of the Bayeux Tapestry sums up events succinctly, showing a disorganised gaggle of fyrdsmen and some figures on horses making themselves scarce, accompanied by the title ET FUGA VERTERUNT ANGLI – ‘and the English turned in flight’.

William was victorious, though at no small cost. At least several thousand of his army lay dead or wounded. But although he had won a decisive battle, the war was by no means over. Two of Harold’s northern Earls, the powerful brothers Edwin and Morcar, still lived. The Anglo-Saxon administrative system and government, the Witengamot, still existed, as did the ecclesiastical posts (and influence) of pro-English churchmen like Stigand and Ealdred – the archbishops of Canterbury and York respectively. In the aftermath of Hastings, a young man whom Harold had largely overshadowed was féted as King by the Witan – the young Eadgar Ætheling, Edward the Confessor’s nephew and son of Edward the Exile, who had died shortly after returning to England. Though how committed the English nobility were to Eadgar’s cause is hotly debated by historians, it is worth noting that resistance to the Normans continued apace through the remainder of 1066 and beyond. An attempt by William to enter London was repulsed, and he was effectively forced to bypass the capital – stamping out uprisings and pockets of resistance as he fought his way along the Thames Valley. Even after the submission of Stigand and the Witan at what is today Berkhampstead, Hertfordshire, and his coronation on Christmas Day of 1066, William still faced acute problems in England. The legendary Saxon nobleman Hereward launched attacks from his base in the Cambridgeshire fens until his defeat in around 1070, while in the southwest of England Harold Godwinson’s fugitive sons, assisted by the Irish, stirred up rebellion in Devon and Cornwall. Although William ultimately retained his grasp over England during this transitory period, he was certainly worked hard in this regard.

William’s coronation and perseverance against the rebellions which dominated his early reign effectively marked the end of what historians refer to as Anglo-Saxon England. Although many of the key governmental institutions, procedures and administrative elements were retained – the Norman invasion did in many respects irreversibly change aspects of daily life forever. This is particularly visible in the realms of both social structure and linguistics. The Anglo-Saxon elite were largely dispossessed of their lands in the aftermath of 1066, these being given over wholesale to Norman supporters of William. The new landowning noble classes were demarcated by language as well as origin, speaking French rather than English – and indeed for centuries after 1066, the dominant tongue of the ‘English’ nobility remained French. By 1075, every earldom was held by a Norman – and by 1096 there were no English-born bishops either. Those of native birth were increasingly being relegated to even more minor administrative or ecclesiastical posts, if any. Perhaps one of the most interesting changes as a result of the Norman invasion was largely indirect – effectively, an Anglo-Saxon diaspora was created, with many nobles choosing to leave England and sail in large numbers for Byzantium in order to join the legendary Varangian guard. In the years following 1066, the number of members deriving from England increased dramatically.

It is interesting to consider, as a final thought, that had Edwin and Morcar not lost the battle of Fulford, had Harold not had to march his troops up and down the length of the country within the space of a fortnight, and had his over-eager troops not broken ranks to pursue the retreating Normans, Anglo-Saxon England might yet exist – with all of Wiliam’s hopes and dreams (and perhaps William himself) lying dead in the dust of Southern England. As always with history, the devil is in the detail.