The Ropsley Hoard

THE BEGINNING: AD 150-152

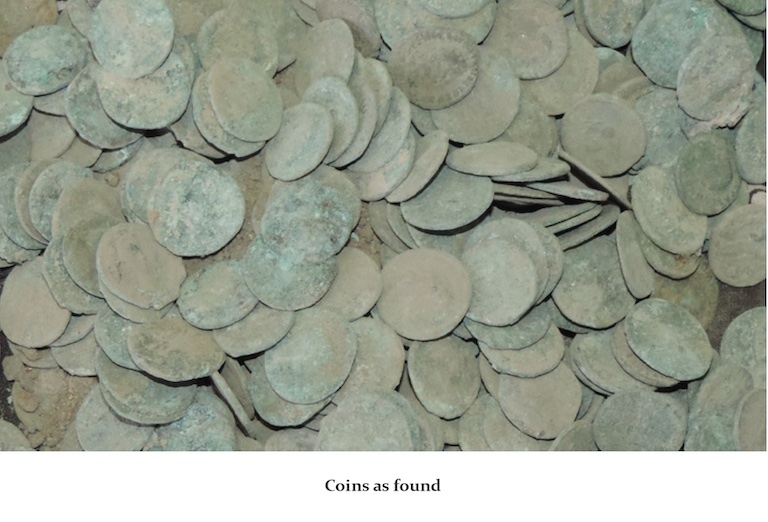

Sometime, during AD 150-152 in the North Eastern corner of the Roman province of Britannia, a citizen was compelled to bury his hoard of 522 silver denari, equivalent in value to around £12,500 in modern day currency. A substantial amount given that a Roman soldier would have been paid around 300 denari per year.

What compelled him to bury the hoard we can only imagine; was it for safe keeping while he headed to market in nearby Ancaster (Causennis), just a short trip up Ermine street or had he been asked to head north and help with the trouble caused by the Caledonians near Hadrian’s Wall? Perhaps they were stolen by a mischievous slave who was then caught, sold and could never return to recover his loot. Who knows but, for certain, these coins were not recovered, at least not in Roman times.

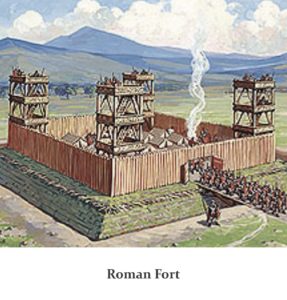

Just north of the find spot is the Roman town of Ancaster (Causennis), this was a small town by Roman standards but still had a forum, town defences and Roman military presence. The Romans built a fort over an Iron Age settlement sometime in the 1st century AD. It lay on Ermine Street, a major Roman road heading north from Londinium (London) and, after the army left, expanded rapidly in the early 2nd century into a small town. Not much is known about life in the town, but industry included pottery production and interestingly, coin forgery. There may have been a sculptor’s workshop as some fine carvings have been discovered.

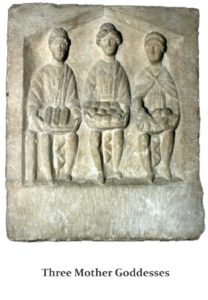

Just north of the find spot is the Roman town of Ancaster (Causennis), this was a small town by Roman standards but still had a forum, town defences and Roman military presence. The Romans built a fort over an Iron Age settlement sometime in the 1st century AD. It lay on Ermine Street, a major Roman road heading north from Londinium (London) and, after the army left, expanded rapidly in the early 2nd century into a small town. Not much is known about life in the town, but industry included pottery production and interestingly, coin forgery. There may have been a sculptor’s workshop as some fine carvings have been discovered. This includes a Deae Matres (The Three Mother Goddesses) sculpture and altar from a religious precinct. Excavations have also found a cemetery containing more than 250 Roman burials, including 11 stone sarcophagi suggesting that people of some wealth lived nearby. A dig by archaeological television programme Time Team in 2001 revealed a cist burial partly constructed with a re-used inscription to the god Viridios. The dig also uncovered Iron Age to 3rd-century pottery, a 1st-century brooch and some of the Roman town wall.

This includes a Deae Matres (The Three Mother Goddesses) sculpture and altar from a religious precinct. Excavations have also found a cemetery containing more than 250 Roman burials, including 11 stone sarcophagi suggesting that people of some wealth lived nearby. A dig by archaeological television programme Time Team in 2001 revealed a cist burial partly constructed with a re-used inscription to the god Viridios. The dig also uncovered Iron Age to 3rd-century pottery, a 1st-century brooch and some of the Roman town wall.