The Colkirk Hoard of Roman Silver Siliqua

From the final years of the 4th & 5th century AD, a remarkable phenomenon unparalleled anywhere else in the Roman empire began to occur in Britain.

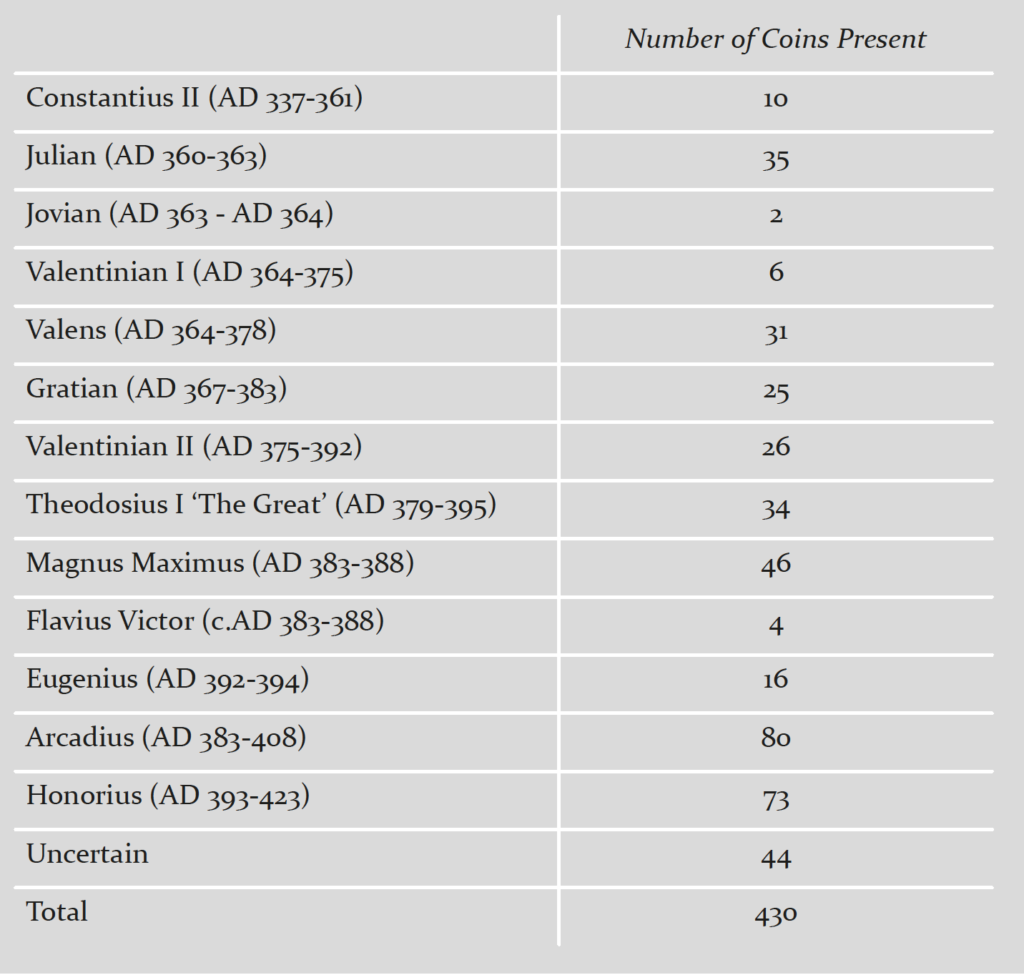

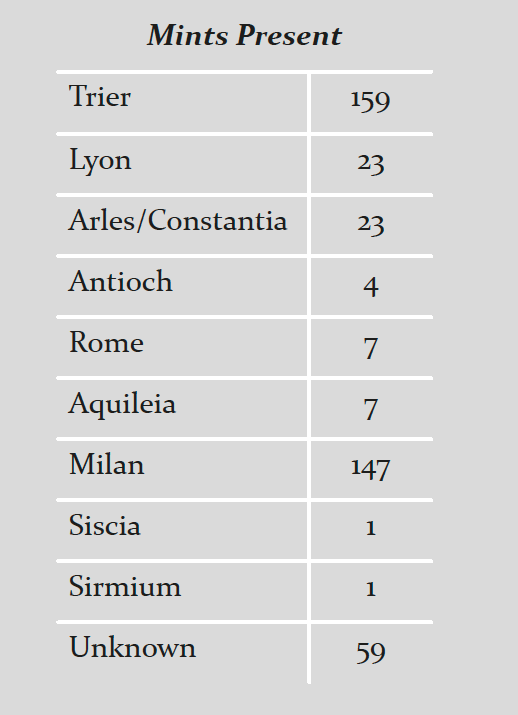

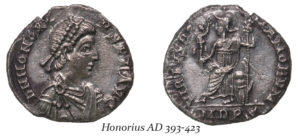

Running across a swathe of the country extending from Yorkshire in the north, down to Norfolk in the east and then as far as Wiltshire in the west, people began to bury hoards. These varied wildly in size, materials and content. While some consisted of small groups of siliquae (late Roman silver coins), others were decidedly more extensive. Sets of silver tableware and large mixed deposits of high-status jewellery occurring alongside hundreds or thousands of silver and gold coins are all represented within the corpus of hoards secreted away during this period.

It is only too evident that these deposits were never recovered by those who buried them – surfacing many centuries later when inadvertently dragged up by ploughshares or recovered by metal detectorists.

Some interesting regional trends are visible. For example, hoards of silver tableware and objects tend to cluster in East Anglia, while deposits of solely gold or silver coins have their focus in the southwest. Finds such as those from Stanchester, Hoxne, Mildenhall, Water Newton, Patching, East Harptree and Gussage All Saints evoke familiar images of glittering treasure – coins, jewellery, lavish dinner services and bullion. Many have now been acquired for public benefit by institutions, and indeed the Hoxne and Mildenhall treasures (to name two of the most famous) can be seen on display in the British Museum.

This booklet presents one of the smaller (yet, as we shall see, just as important) coin hoards dating to this period.